Saturday, December 25, 2010

Monday, January 3, 2011

Thursday, December 16, 2010

Thursday and Friday, December 16-17

THE DIGITAL STORY OF NATIVITY - ( or Christmas 2.0 )

Tuesday, December 14, 2010

Hakuna Matata(English)

Wednesday, December 15, 2010

Monday, December 13, 2010

Tuesday, December 14, 2010

Sunday, December 12, 2010

Monday, December 13, 2010

Thursday, December 09, 2010

Friday, December 10, 2010

Straight No Chaser - 12 Days (original from 1998)

Wednesday, December 08, 2010

Thursday, December 9, 2010

Characters to Know

Hamlet, Prince of Denmark

Hamlet the Elder (ghost), Fortinbras the Elder, Old Norway: The Trifecta of Old

Claudius

Gertrude

Laertes

Ophelia

Players and Player King

Rosencrantz and Guildenstern

Horatio

Reynaldo

Yorick

Themes to Know and Understand

Denmark as a garden

The play-within-the-play motif (know both titles--"The Murder of Gonzago" and "Mousetrap")

Rottenness

The role of the supernatural

The role of philosophy

The significance of three sons mourning three dead fathers

Graveyard imagery

Sexual imagery

Wednesday, December 8, 2010

Sunday, December 05, 2010

Tuesday, December 7, 2010

Monday, December 6, 2010

Thursday, December 02, 2010

Friday, December 3, 2010

Wednesday, December 01, 2010

Hamlet, Explained: TS Eliot Denigrates Art

You can find this essay in its entirety at this website; Eliot's work is in the public domain, due to the elapsed copyright date: http://www.bartleby.com/200/sw9.html

T.S. Eliot (1888–1965). The Sacred Wood: Essays on Poetry and Criticism. 1922.

Hamlet and His Problems

FEW critics have even admitted that Hamlet the play is the primary problem, and Hamlet the character only secondary. And Hamlet the character has had an especial temptation for that most dangerous type of critic: the critic with a mind which is naturally of the creative order, but which through some weakness in creative power exercises itself in criticism instead. These minds often find in Hamlet a vicarious existence for their own artistic realization. Such a mind had Goethe, who made of Hamlet a Werther; and such had Coleridge, who made of Hamlet a Coleridge; and probably neither of these men in writing about Hamlet remembered that his first business was to study a work of art. The kind of criticism that Goethe and Coleridge produced, in writing of Hamlet, is the most misleading kind possible. For they both possessed unquestionable critical insight, and both make their critical aberrations the more plausible by the substitution—of their own Hamlet for Shakespeare's—which their creative gift effects. We should be thankful that Walter Pater did not fix his attention on this play. | |

Two recent writers, Mr. J. M. Robertson and Professor Stoll of the | |

Qua work of art, the work of art cannot be interpreted; there is nothing to interpret; we can only criticize it according to standards, in comparison to other works of art; and for "interpretation" the chief task is the presentation of relevant historical facts which the reader is not assumed to know. Mr. Robertson points out, very pertinently, how critics have failed in their "interpretation" of Hamlet by ignoring what ought to be very obvious: that Hamlet is a stratification, that it represents the efforts of a series of men, each making what he could out of the work of his predecessors. The Hamlet of Shakespeare will appear to us very differently if, instead of treating the whole action of the play as due to Shakespeare's design, we perceive his Hamlet to be superposed upon much cruder material which persists even in the final form. | |

We know that there was an older play by Thomas Kyd, that extraordinary dramatic (if not poetic) genius who was in all probability the author of two plays so dissimilar as the Spanish Tragedy and Arden of Feversham; and what this play was like we can guess from three clues: from the Spanish Tragedy itself, from the tale of Belleforest upon which Kyd's Hamlet must have been based, and from a version acted in Germany in Shakespeare's lifetime which bears strong evidence of having been adapted from the earlier, not from the later, play. From these three sources it is clear that in the earlier play the motive was a revenge-motive simply; that the action or delay is caused, as in theSpanish Tragedy, solely by the difficulty of assassinating a monarch surrounded by guards; and that the "madness" of Hamlet was feigned in order to escape suspicion, and successfully. In the final play of Shakespeare, on the other hand, there is a motive which is more important than that of revenge, and which explicitly "blunts" the latter; the delay in revenge is unexplained on grounds of necessity or expediency; and the effect of the "madness" is not to lull but to arouse the king's suspicion. The alteration is not complete enough, however, to be convincing. Furthermore, there are verbal parallels so close to theSpanish Tragedy as to leave no doubt that in places Shakespeare was merely revising the text of Kyd. And finally there are unexplained scenes—the Polonius-Laertes and the Polonius-Reynaldo scenes—for which there is little excuse; these scenes are not in the verse style of Kyd, and not beyond doubt in the style of Shakespeare. These Mr. Robertson believes to be scenes in the original play of Kyd reworked by a third hand, perhaps Chapman, before Shakespeare touched the play. And he concludes, with very strong show of reason, that the original play of Kyd was, like certain other revenge plays, in two parts of five acts each. The upshot of Mr. Robertson's examination is, we believe, irrefragable: that Shakespeare's Hamlet, so far as it is Shakespeare's, is a play dealing with the effect of a mother's guilt upon her son, and that Shakespeare was unable to impose this motive successfully upon the "intractable" material of the old play. | |

Of the intractability there can be no doubt. So far from being Shakespeare's masterpiece, the play is most certainly an artistic failure. In several ways the play is puzzling, and disquieting as is none of the others. Of all the plays it is the longest and is possibly the one on which Shakespeare spent most pains; and yet he has left in it superfluous and inconsistent scenes which even hasty revision should have noticed. The versification is variable. Lines like Look, the morn, in russet mantle clad,

Sir, in my heart there was a kind of fighting

| |

The grounds of Hamlet's failure are not immediately obvious. Mr. Robertson is undoubtedly correct in concluding that the essential emotion of the play is the feeling of a son towards a guilty mother: [Hamlet's] tone is that of one who has suffered tortures on the score of his mother's degradation.... The guilt of a mother is an almost intolerable motive for drama, but it had to be maintained and emphasized to supply a psychological solution, or rather a hint of one.

| |

The only way of expressing emotion in the form of art is by finding an "objective correlative"; in other words, a set of objects, a situation, a chain of events which shall be the formula of that particular emotion; such that when the external facts, which must terminate in sensory experience, are given, the emotion is immediately evoked. If you examine any of Shakespeare's more successful tragedies, you will find this exact equivalence; you will find that the state of mind of Lady Macbeth walking in her sleep has been communicated to you by a skilful accumulation of imagined sensory impressions; the words of Macbeth on hearing of his wife's death strike us as if, given the sequence of events, these words were automatically released by the last event in the series. The artistic "inevitability" lies in this complete adequacy of the external to the emotion; and this is precisely what is deficient in Hamlet. Hamlet (the man) is dominated by an emotion which is inexpressible, because it is in excess of the facts as they appear. And the supposed identity of Hamlet with his author is genuine to this point: that Hamlet's bafflement at the absence of objective equivalent to his feelings is a prolongation of the bafflement of his creator in the face of his artistic problem. Hamlet is up against the difficulty that his disgust is occasioned by his mother, but that his mother is not an adequate equivalent for it; his disgust envelops and exceeds her. It is thus a feeling which he cannot understand; he cannot objectify it, and it therefore remains to poison life and obstruct action. None of the possible actions can satisfy it; and nothing that Shakespeare can do with the plot can express Hamlet for him. And it must be noticed that the very nature of the données of the problem precludes objective equivalence. To have heightened the criminality of Gertrude would have been to provide the formula for a totally different emotion in Hamlet; it is just because her character is so negative and insignificant that she arouses in Hamlet the feeling which she is incapable of representing. | |

The "madness" of Hamlet lay to Shakespeare's hand; in the earlier play a simple ruse, and to the end, we may presume, understood as a ruse by the audience. For Shakespeare it is less than madness and more than feigned. The levity of Hamlet, his repetition of phrase, his puns, are not part of a deliberate plan of dissimulation, but a form of emotional relief. In the character Hamlet it is the buffoonery of an emotion which can find no outlet in action; in the dramatist it is the buffoonery of an emotion which he cannot express in art. The intense feeling, ecstatic or terrible, without an object or exceeding its object, is something which every person of sensibility has known; it is doubtless a study to pathologists. It often occurs in adolescence: the ordinary person puts these feelings to sleep, or trims down his feeling to fit the business world; the artist keeps it alive by his ability to intensify the world to his emotions. The Hamlet of Laforgue is an adolescent; the Hamlet of Shakespeare is not, he has not that explanation and excuse. We must simply admit that here Shakespeare tackled a problem which proved too much for him. Why he attempted it at all is an insoluble puzzle; under compulsion of what experience he attempted to express the inexpressibly horrible, we cannot ever know. We need a great many facts in his biography; and we should like to know whether, and when, and after or at the same time as what personal experience, he read Montaigne, II. xii., Apologie de Raimond Sebond. We should have, finally, to know something which is by hypothesis unknowable, for we assume it to be an experience which, in the manner indicated, exceeded the facts. We should have to understand things which Shakespeare did not understand himself. |

I have never, by the way, seen a cogent refutation of Thomas Rymer's objections to Othello. [back]

Thursday, December 2, 2010

Tuesday, November 30, 2010

Wednesday, December 1, 2010

Monday, November 29, 2010

Tuesday, November 30, 2010

Sunday, November 28, 2010

Monday, November 29, 2010

Wednesday, November 24, 2010

Cheer Pressure: Third Annual Edition

This post is strictly meant to be helpful.

Did you know that the average American family will go into debt over holiday presents?

And that the average holiday expenditure per family of four is over one thousand dollars?

And that everyone seems to want something out of you on the holiday trainwreck--whether it be get-togethers, expanded tipping for the people who provide services throughout the year, or the incessantly tinntinnabulous bellringers outside of local constabulatories?

So, Hilley has solutions for you. Of course, I'd like to suggest gently that we just stop with all of the gift-giving, but that would be really hypocritical of me since I lurve giving presents to people. LOVE IT. I love all of it--selecting them, wrapping them lovingly a la Martha Stewart, and watching with glee as the recipient(s) opens my carefully-contemplated schwag. Love it.

What I don't love is the pre-holiday anxiety about how in the heck I plan to pay for all of this material joy.

So, short of standing on street corners with a sign statingWill Conjugate/Edit/Proselytize for Christmas Money, I have been casting about for financially sound holiday solutions for Loved Ones, and I want to share my new-found wisdom with you.

NEW SUGGESTIONS FOR 2010's CONTINUING ECONOMIC CRISIS:

1A. Just tell your friends and family that the recession is hitting you particularly hard, and you will be praying for them/thinking of them/writing poetry in honor of them in lieu of presents. How can anyone argue with that?

1B. Write up lovely cards stating that you donated to The Human Fund in their name to celebrate Festivus.

1C. Just promise to not discuss politics with them for the next twelve months in lieu of a tangible gift. Most of us would appreciate that, especially if your political views are Wrong and theirs are Correct. In their estimation, of course.

1D. Go to sleep on the 23rd and awaken on the 26th, holiday over. Then hit the 80% off sales, beg for forgiveness, and enjoy the savings. (My trig teacher at LMHS convinced his two kids that Christmas was 12/29 each year so he and his wife could deep-discount their gifts. Lasted until the kids could read calendars. . .)

Now on to the suggestion list from last year, reposted in lieu of a present to many, many of you, because I love you and because I apparently love handbags more than I love you. My apologies. And NONE of these places have given me anything to write about them, so please don't accuse me of being overly commercial.

1. Do not re-gift, unless you are ABSOLUTELY certain that the original gift-giver has moved to Saskatchewan and that the new recipient will not be posting pictures of the new bling on Facebook or whatever. In our newly savvy techno-age, there are a myriad of ways in which a regifter can be busted. I speak from vicarious experience, since my BFF has regifted virtually every gift I've ever given her. . .to me. In recent years I've gotten smart and only given her expendables, like face cream or a gift card. You'd be amazed at what that woman is willing to return, and in what condition, and without what receipts. She is so lucky I love her. (Note from 2010: For her birthday on 11/21, I gave her something I liked just in case it finds its way under my tree on the 25th.)

2. Homemade presents are always great, but be careful that you don't end up spending more money on the materials than you would have on some pre-made stuff of similar ilk. Six years ago, BFF and I went soap-crazy and made homemade soaps for all of our beloveds. While some of the soaps were well-received (and some were hilarious--like the one we filled with toenail clippings, and the one we filled with leftover Ramen Noodles) the average cost per bar of soap was over eight bucks. In other words, NOT COST-EFFICIENT.)

3. Hit the dollar spot at T____ (national discount chain with a bullseye logo). They have amazing stuff there, and, more importantly, they have really good-quality gift wrap and bows for A DOLLAR. Failing that, start saving unusual shopping bags, pieces of paper, and fabric for unique gift-wrap. Those card-stock, unrecycle-able community newsletters? Great giftwrap, guaranteed to raise eyebrows! And I'd also like to point out that P___ (local grocery store chain) has nice reusable grocery bags with festive prints--pop a gift in, close it, and you have two gifts in one!

4. For those of you who are girly: This website has Sephora-level quality cosmetics for a dollar apiece, and gift sets in the five/ten/fifteen dollar range:http://www.eyeslipsface.com. Their packaging is good and the shipping prices are decent. Lately, they've been offering FREE SHIPPING. Whoohaa.

5. For those of you are super-girly, try this website, where every piece of jewelry is "free" (actually, 6.99 for shipping, but when it arrives the stamp says 82 cents, but whatever):www.silverjewelryclub.com

6. For those of you with a slightly higher budget and a quirky sense of humor, try any of these websites:www.fredflare.com,www.blueq.com, andwww.perpetualkid.com.

7. There is absolutely nothing wrong with findingsomething vintage and amazing at Goodwill Boutique--especially the one near Park Avenue in Winter Park. Dechoes is good, too, if you are looking for something in particular--they closed the one on Curry Ford, but the ones on Edgewater and Colonial Drive are still there, and still awesome. Local churches also have thrift stores with a huge array of finds for relatives and friends.

8. If you have a slightly higher discretionary income and want your money to go to good use, you can't beat the fair-trade handmade bags at Amani Ya Juu, which I got for my mom, sister, and sister-in-law last season. All of the proceeds go to the women in the tribe. Special thanks to the Chitty family for their hands-on work with this organization. www.amaniafrica.org.

9. You cannot underestimate the power of a deed or an event. Offer to take a younger sibling out for an afternoon, or pack a picnic for your sig-o, or offer to help the disorganized adult in your life redo her filing system, or whatever. Write the offer in a nice card and revel in the money you're saving--and the real impact you might be creating.

10. Also, don't underestimate the power of your own talents. Burn a DVD of a film you've made, or a performance in which you participated, and include a detailed write-up; take your oddest/most innovative playlist and commemorate it on a CD; make a painting, or write a poem, or short story; if you have leftover art materials from previous craft projects, get creative and see what you can make. Grandparents will squee in glee; little kids will love it; your friends may tease you but secretly adore it.

Final note: You really do not have to get presents for teachers, although the greediest among us do love bling. Overweening giftage can be awkward, and the majority of us would really prefer a heartfelt note wishing us a nice holiday and saying how the class is going so far. Save your money; buy your girl/boyfriend something, go to the movies, go buy a book and READ IT. Then write me a note about how you used the money you almost blew on an apple paperweight or bookmark and how much you really love literature, and we're gravy. Of course, if you are a millionaire, I would like to mention how much I like Starbucks.

Happy Holidays, everyone!

Thursday, November 18, 2010

Friday, November 19, 2010

Wednesday, November 17, 2010

Reduce/Reuse/Recycle: Hamlet, Explained Part II

In which we look at individual scenes and particular details you should note.

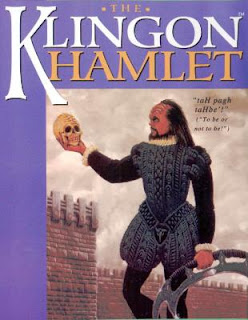

Did you know that Hamlet has been translated into Klingon? Really! I had a copy once, but it took a walk right out of my classroom. Oh,Qu'vatlh guy'cha b'aka!

Act I, scene i

We open with a ghost scene; fascinating that the first words of the play are "Who's there?" Suspicion dominates from the very beginning of the play; several guards, some of whom have oddly Italian names, have seen a ghost walking and have asked the trusted Horatio to come take a look. While they wait, Horatio engages them with the protracted tale of how the Norwegian-Danish conflict thus far had been resolved prior to the play's beginning.

Elements to look for: external and internal conflict; supernatural imagery

Act I, scene ii

Claudius, the new King of Denmark, begins this scene with a marvelously nuanced speech about his ascension to the throne; he refers to his bride as "th' imperial jointress to this warlike state." in other words--power comes through Gertrude. Good to know. No one in Denmark seems particularly perturbed by the haste with which the two have married (with mirth in funeral and dirge in marriage) except for the emo boy in the corner, who promptly gets into it with his new stepfather. "Cast thy nighted color off," entreats his mom; after all, how much mourning can a new bride tolerate? He shrugs and promises to obey her, but gives little reply to Claudius's twin edicts that Hamlet A) stop mourning, as it's bringing everyone down, and B) stay here in Denmark, instead of popping back to Wittenberg for further graduate studies in melancholia.

This scene truly takes flight, though, in Hamlet's remarkable first soliloquy--our first gaze into his soul, and our first look at the honest, un-socialized Danish prince. He is profoundly depressed by his father's death and his mother's seemingly oblivious reaction to it. How could she marry so quickly, and to his father's brother? He ends the ruminations when he greets Horatio, an old friend whom he had apparently not seen in some time. When Horatio informs Hamlet of the ghost's appearances on the castle walls, Hamlet perks up and seems eager to investigate this happening for himself. Despite his trepidation (Renaissance thinkers were notoriously skittish about such things) his curiosity outweighs his fear, and he plans to join Horatio and the other guards at the top of the castle after eleven that very night.

Elements to look for: allusions to Greek mythology and the Bible; Claudius's silky diplomacy; Gertrude's maternal requests; Hamlet's use of language alone and with others; color imagery

Act I, scene iii

The scene switches to Polonius's chambers within the castle. Laertes is earnestly talking to his younger sister, and telling her that Hamlet is not a long-term option for her, as he is "subject to his birth." Ophelia, recognizing her brother's genuine concern and affection for her, responds with gentle humor, telling him not to be hypocritical and to watch his own sexual behavior. Since he is heading off to "study" in Paris, we can only assume that he is a bit of a party boy. Polonius himself bursts into the room, chastising Laertes for packing too slowly, then "helps" him by giving him tons of advice on living. Some of it is actually pretty solid--don't get in a fight, but if you do, win; don't lend out money; be careful whom you trust. The most interesting tidbit is when he ways "to thine own self be true," which may as well be engraved on Polonius's self-serving heart. Then, Polonius browbeats his daughter into discussing Hamlet with him, too, and he urges her to "tender yourself more dearly." If his daughter were to be publicly associated with Hamlet's desires, it could be detrimental to his own ambitions.

Elements to look for: metaphors, platitudes, the relationship between father/son and father/daughter, sexual mores of the Renaissance as expressed to both genders

Act I, scene iv:

This comparatively brief scene takes place atop the castle walls. Marcellus, Bernardo, Francisco, and Horatio accompany Hamlet in much conversation before the ghost appears. When the ghost does manifest itself, the brave soldiers lose their bravado and attempt to force Hamlet to stay with them, fearing his destruction if the ghost is a demon. Hamlet threatens his friends with his sword and runs after the ghost. Time loses all meaning as Horatio and the men "search" for Hamlet, presumably while the next scene unfolds. This scene hosts the famous "Something is rotten in the state of Denmark" line, as intoned by Marcellus.

Elements to look for: visual imagery; Renaissance attitudes toward the supernatural

Act I, scene v:

Hamlet confronts the ghost of his father, who is fairly talkative for a armor-clad spectre. Hamlet the Elder reveals that even though the party line claimed he died after being bitten by a serpent, he's actually the victim of fratricide--the oldest Biblical crime. His brother Claudius had waited until he had fallen asleep in his orchard (as was my custom) and poured poison in his ear, killing him with wrenching agony and without an opportunity to make confession. Thus murdered, "with all my sins upon my head/No reckoning made," the ghost must spend each day in Purgatory, suffering, and each night walking the earth. He demands that his son avenge his murder, but leave his mother "to Heaven." Hamlet, spurred to revenge, seems eager to get to work, and once reunited with his peeps, forces them to swear on his sword to keep silent about his plan. He will pretend to be crazy so people will leave him alone--not the greatest plan in the world for someone a few credits shy of a PhD. His "antic disposition" will entertain the Danish for many weeks to come.

Elements to look for: religious symbolism, father/son separation anxiety, serpent imagery

mupwI' yI'uchtaH! (Good night!)

Reduce/Reuse/Recycle: Hamlet, Explained

Reduce/Reuse/Recycle: Reprinted from 2008

Hamlet, Explained (Part One of an Occasional Series)

Hamlet is more complicated than Macbeth, with higher diction levels--but most of the complications arise from the interweaving of several subplots.Macbeth, you will recall, contains one driving narrative thread--the collapse of one man's morality as he ascends in power. Although other motifs and symbols figure within that tragedy, all go back directly to that main plot. Hamlet is far more complicated, with political intrigues, conjectures, and elements of ambiguity there to enhance the text.

Some things to consider:

1. Hamlet may or may not be insane, which complicates your understanding of his role and his use of language immensely. Note how he pops back and forth effortlessly from prose (paragraph form) to unrhymed iambic pentameter (blank verse) to rhyming couplets, regardless of his audience. The only solidity we get from him is contained in his soliloquies, which are confusing enough due to his high level of education and insight.

2. Claudius is not a completely "bad" bad guy--he is greedy, narcissistic, venial, selfish, and did a very, very bad thing. His sin is Biblical (fratricide) and was motivated by the greatest of all human motivations--jealousy. He has moved into his older brother's life--wife, crown, title--and seems competent in governance if not in morality. On some level, he wants Hamlet's cooperation and approval, but he goes about trying to "parent" the errant prince in increasingly uneven and careless ways.

3. Gertrude, the DSQ, is probably more ignorant than dumb. There is a difference. She and Ophelia, while more complex than other female stock characters in Elizabethan theater, are still two-dimensional compared to the men who rule them. Try to see her as a baffled woman attempting to regain a sense of sexual independence and her role might make more sense.

4. Polonius and other courtiers are interfering and obtuse, to the point of obscuring some of the main narrative thread. Every time Polonius is featured in a scene, we are tempted to see him as the commedia dell'artestock character of the "pantaloon"--the foolish old man. (Hamlet himself refers to him as a "tedious old fool.") However, Polonius is critically important to understanding the overriding motifs of duplicity, spying, and dishonesty that govern everything that goes on in Elsinore Castle--and may well have been going on even before the death of Hamlet the Elder.

And, to further clarify what's been going on thus far, I am going to repost something that appeared in McSweeney's a while ago. I hope that I am not violating copyright; this has made the rounds on Facebook and on several blogs and I am only posting to bring clarity and understanding to my poor, confused students. Here are the first three acts of Hamlet, Facebook- style:

HAMLET

(FACEBOOK NEWS

FEED EDITION).

BY SARAH SCHMELLING

- - - -

Horatio thinks he saw a ghost.

Hamlet thinks it's annoying when your uncle marries your mother right after your dad dies.

The king thinks Hamlet's annoying.

Laertes thinks Ophelia can do better.

Hamlet's father is now a zombie.

- - - -

The king poked the queen.

The queen poked the king back.

Hamlet and the queen are no longer friends.

Marcellus is pretty sure something's rotten around here.

Hamlet became a fan of daggers.

- - - -

Polonius says Hamlet's crazy ... crazy in love!

Rosencrantz, Guildenstern, and Hamlet are now friends.

Hamlet wonders if he should continue to exist. Or not.

Hamlet thinks Ophelia might be happier in a convent.

Ophelia removed "moody princes" from her interests.

Hamlet posted an event: A Play That's Totally Fictional and In No Way About My Family

The king commented on Hamlet's play: "What is wrong with you?"

Polonius thinks this curtain looks like a good thing to hide behind.

Polonius is no longer online.

(I will post the next two acts after we have read further. No plot spoilers here, unless you've seen The Lion King!)

And here is Hamlet, South Park style:

Another element that might help you understand this play:

Three Reasons Why Shakespeare is Hard to Understand

1. Grammar. Particularly in Hamlet, Elizabethan grammar is different than Standard American English. One common element we see in conversations between characters is inversion, which is easy enough to follow in simple declarative sentences (Go you here today?) but is harder to parse in complex, lengthy expressions--the ones favored by our titular hero. This is where the modern English version can help you, if read WITH the Elizabethan text. (Guys, I'm sorry, but I'm never going to lose my fascination with asking you to identify quotes.)

2. Archaic words. What is a bodkin? Who or what are fardels? What is aquietus? Shakespeare frequently uses words that are no longer in our vernacular, and I'm not merely talking about thou, thee, and whilst. I will continue to define words as I can in class, but out of class in private reading you might need to consistently avail yourself of the footnotes available in every edition. Also, I will be publishing a glossary of Hamlet words, but I have to warn you--it's looooooooong.

(Note: A bodkin is a dagger, and fardels are burdens, and a quietus is the conclusion of one's life.)

3. Words with different meanings. The best example of this is when Hamlet confronts Ophelia in her closet, which at the time simply meant a private chamber or room. A very different visual image than Hamlet, in dirty stockings and no hat, grabbing her amid a sea of coat hangers, eh? If you are hit by the "confusement" train, be sure that the word you think you are reading in its context actually means what you, a 2009 reader, thinks it means. Again, make liberal use of footnotes.